Trekking the Wintry North Woods with Venerable Bishop Baraga

The snow glistens and glimmers as the sunshine sparkles and dances off of the soft drifting banks. The snow is pressed down in hushed crunches, leaving large, shallow imprints like oblong saucers in a trail behind the winter wanderer. This peaceful scene is familiar to snowshoers, those who strap contraptions shaped like beaver tails to the bottom of their boots making their feet big like lynx paws. The large surface area (of both snowshoes and lynx paws alike) distributes weight, allowing the snow trekker to float on top of the first few inches of the deep snow.

Snowshoes have been around for thousands of years and come in many different shapes, styles, and materials. From the lightweight plastic and aluminum ones you can find today, to the rawhide and white ash ones that have been made for centuries by the Ojibwe, people have constantly been finding ways to adapt to the influx of snow that slows down winter travel.

Left: Traditional Ojibwe Snowshoes made of White Ash and Rawhide. The pointed tips help to break through icy, crusty snow and avoid snagging in brush.

Right: Modern lightweight snowshoe models available for use at the CEC.

For those who have experienced deep snow without snowshoes, it doesn’t take long to tire of “postholing”- the exhausting practice of schlepping your legs out of the deep snow, hoisting them up, just to step forward and sink back down and repeat the whole process over again. While it is much easier with snowshoes, traversing any trails in winter is a workout regardless!

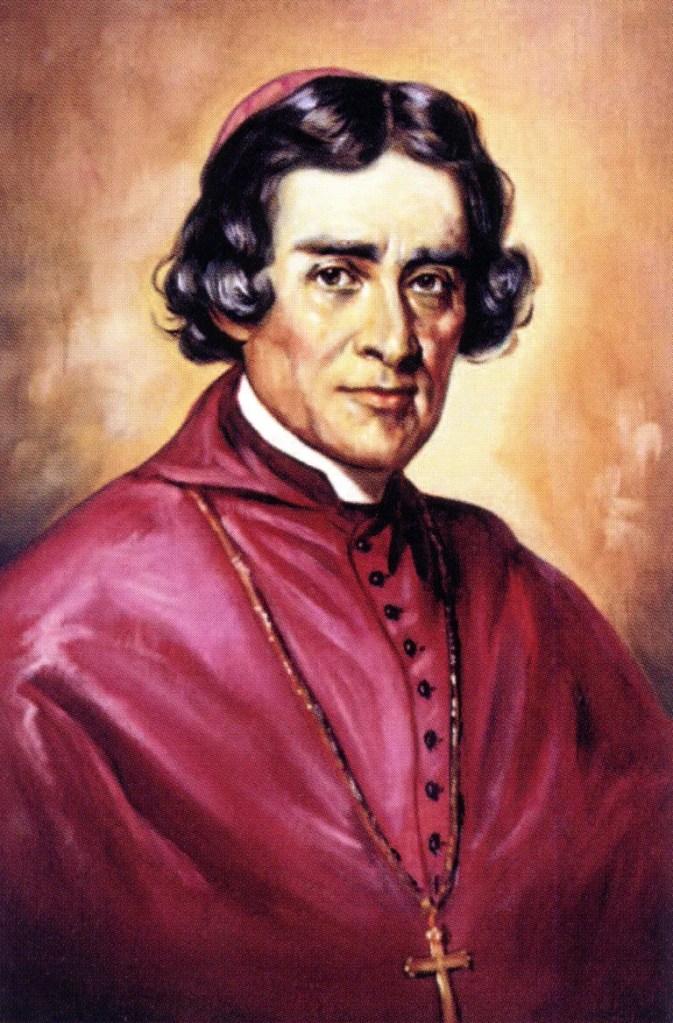

It puts into perspective the incredible journeys that Bishop Frederic Baraga made in the upper peninsula of Michigan as a priest and bishop in the mid1800s. Originally from Slovenia, Father Baraga was born on June 29, 1797. A bright young man, Fredric learned many languages including German, Slovenian, French, and Latin. He became a lawyer after studying at the University of Vienna, but felt the call to the priesthood and joined the seminary shortly thereafter. By age 26, he was ordained Father Baraga and served the people of his diocese for several years. Eventually though, he felt drawn to become a missionary priest and in 1830 set sail for America!

He began his work in Cincinnati, studying the Ottawa language. His aptitude for linguistics allowed him to pick it up quickly, and in 1831 he was asked to go to an Ottawa Indian mission at L’Arbre Croche (present-day Cross Village, Michigan). He grew very close with the people and came to know them, their way of life, and language in a deep way. In 1837, he published Otawa Anamie-Misinaigan, the first book written in the Ottawa language, which included a Catholic catechism and prayer book.

His ministry wasn’t limited to the Ottawa people though. Fr. Baraga established missions all over the U.P. and had a deep love that is evident in his action and interactions with all of the people he encountered. In his work with the Ojibwe, he not only learned their language, but published pastoral letters both in English and Ojibwe in addition to translating over 100 Catholic Hymns in the Ojibwe language which are still used today. When the government tried to relocate and force the Ojibwe from their land, Fr. Baraga was a staunch advocate for them and worked to ensure they could retain their home.

Additionally, as the German and Irish immigrants moved to the Upper Peninsula to work in the copper mines, Fr. Baraga would minister to them and their communities. His role as a shepherd to such a large and distant flock meant that he traveled extensively. In the summertime, this was often by foot or canoe, but winter in Michigan’s upper peninsula can bring over 300 inches of snow per year, so snowshoeing was his method of transportation! In February of 1845, it was recorded that Fr. Baraga walked over 600 miles in the course of five weeks! This dedication and grit earned him the nickname “The Snowshoe Priest.”

In 1853, Fr. Baraga was ordained Bishop of Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, now the diocese of Marquette, Michigan. He worked to bring more priests in to minister to the area, but it was a challenge to find those who could minister to both the Native American and immigrant communities. Not surprisingly, Bishop Baraga’s physical stamina and linguistic aptitude were difficult to match!

He continued ministering and snowshoeing to his flock late into his sixties. In 1866, when visiting Baltimore for a Bishops conference, he suffered a severe stroke. He immediately asked to go back to Michigan to be home among the people of his flock. His health fluctuated from that point on until he passed away in 1868 among the people he loved and had dedicated his life to.

Left: The shrine of Bishop Baraga in Michigan’s upper Peninsula.

Middle: Man standing by one of the snowshoes that are used in the Statue of Bishop Baraga at his shrine.

Right: A cross on the shores of Lake Superior in Minnesota honoring Bishop Baraga.

The city of Marquette, Michigan declared the day of a his funeral a civic day of mourning. Despite the cold temperatures and blizzard like conditions, the church was filled to capacity and then some as people, Catholic and non-Catholic alike, spilled out to honor the man they believed to be a saint in their midst.

Today you can visit the shrine of Bishop Baraga in L’Anse, MI where a giant copper statue stands of the priest and his trusty pair of snowshoes. On the north shore of Lake Superior, in Minnesota, you will find a Fr. Baraga memorial cross. Whether on the shores of Lake Superior where he ministered or on the trails here at the CEC, call to mind the humble, hardworking, and adventurous life of venerable Bishop Baraga the next time you strap on your snowshoes. Venerable Bishop Baraga…Pray for us!

Come snowshoe at the CEC! Rentals are free for members or $5/day for non-members.